This article originally published on GoDaddy’s Venture Forward website.

While the ongoing COVID-19 crisis has shuttered tens of thousands of small businesses and sent entire economies into tailspins, one cohort of entrepreneurs is proving surprisingly resilient. And, in turn, they’re creating economic stability in their local communities.

They are the operators of millions of digital domain-name websites that GoDaddy, which hosts the sites, labels “ventures.” Our multiyear research project, Venture Forward, found these often-overlooked and uncounted participants in the digital economy helped regions recover more fully from the 2008 recession, and are creating the same sort of buffer during the current crisis.

Ventures are, of course, as diverse as the country they reside in. They’re in every state. They’re rural and urban. They’re run by women and men, full-time business owners, students, retirees, military personnel and part-time workers. They come from every ethnicity and education level.

While the ventures themselves — sometimes just one person working out of a motel to sell handmade candles — are less visible to neighbors and to policymakers who can help them, their importance to their local economies is beginning to emerge. Here are three of their stories.

Related: Online micro-businesses can be an easy economic win for local governments

Out of the fire and into the frying pan

When Zach Sass was laid off from his job as executive chef at a popular Nashville restaurant — a touristy gastropub on the city’s famed Music Row that closed in March — at first, he panicked.

“I have a son, a house, a car, I have bills to pay,” says Sass. “My whole environment came to a stop. That was terrifying. I didn’t know what my next step should be.”

But then came a call from his best friend — “who’s a terrible cook,” Sass says — asking for advice on what to make his girlfriend for an anniversary dinner. Sass hopped on a video call and, using what the guy had in his kitchen, “we made an amazing meal and had a lot of fun chatting,” he says.

That virtual hangout birthed a business. Sass now runs an online venture, Chef Zach Sass, where he teaches homebound chefs how to cook a meal with whatever they have on hand.

Instead, he has students send him pictures of whatever is in their refrigerators, freezers and pantries. Then he comes up with a recipe and gives them a virtual cooking lesson at home.

Since starting in mid-March with only his laptop, a Facebook Portal camera and zero technical savvy, the 31-year-old Sass has taught 50 or more classes. He syncs up with students as far away as Toronto and Mumbai, who pay him in donations that range between $25 and $350.

In the past three months, he’s pulled in at least $5,000, he says. It’s enough to provide a primary income to support himself and his 6-year-old son, whom he cares for full time during the week.

Like many ventures, Sass struggles with marketing, but has found success through social media platforms, media coverage of his business and, more recently, with Facebook and Google’s paid and targeted ads. “It’s all about marketing and putting yourself out there as much as you can,” he says.

To grow his business, Sass needs something he’s never had to seek before — capital. “I definitely want to expand as much as possible and get to a point where I can add more classes and help some of my fellow cooks who are in limbo,” says Sass. “If I can get to the point where I can make this bigger, I can branch out and help them,” he says.

“I knew at one point in my career, and even from the time I was a child cooking with my Italian grandma, that I would end up owning and operating a business around cooking,” he says. “As I’ve always been a chef for other restaurants, I didn’t expect it to be so sudden. But here it is.”

Quarantine and chill

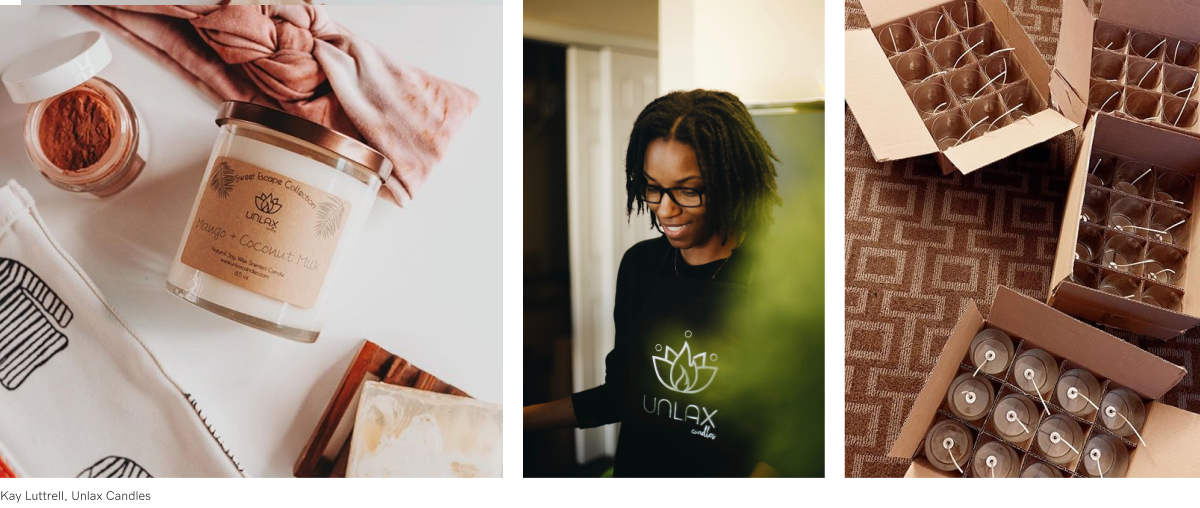

A year ago, the last place Kay Luttrell, a 24-year-old U.S. Navy yeoman, expected to find herself was trapped in a motel room surrounded by partly dried candles. Yet because of COVID-19, that’s exactly how she’s spent the past few weeks.

Luttrell was in Virginia Beach, Virginia, when her base sent all non-essential personnel to work from home in April. By late June, as Luttrell waited for her next posting to start, she was holed up in a motel in nearby Suffolk.

Being home, even a temporary home, allowed Luttrell more time to focus on her online venture, Unlax Candles (a combination of unwind and relax). She had started it in December 2019 as a way to help over-stressed people like herself “chill,” as her website says.

Prior to the pandemic, web traffic and purchases had been rising steadily. Then, with more time on her hands during the pandemic, she took online candle-making classes and found a mentor in the business to advise her on growing her venture. Leading up to Mother’s Day, her mentor advised her to stock up on supplies because the holiday is a busy one for the candle industry.

Not anticipating how the pandemic would impact her business, Luttrell waited too long to purchase supplies. Her vendors — for soy wax, essential oils, glass jars and even shipping — couldn’t fill orders. Many were forced to close their doors or limit accessibility, causing delays for weeks.

Lesson learned: Luttrell shut down marketing ahead of what should have been her biggest sales day of the year. To keep momentum, she over-ordered her next batch of supplies, launched a new collection of candles, and adjusted her online marketing to focus on relief for anxiety brought on by COVID-19.

Today, Lutrell sells candles with scents like Pineapple Sage, Caribbean Teakwood and Sea Salt + Orchids for $15.50 apiece and wax melts (scented cubes that place on wax warmers) for $6. She offers discounts for bulk orders. Her business has grown from about 100 orders per month to about 800 per month, accounting in one recent month for $30,000 in revenue.

The biggest part of her business appeal, Luttrell says, is her personal story about battling anxiety, which she shares on her website and across social media, her primary marketing platform. “I felt like I had a unique story to tell, and if I told it people would respond,” she says.

Recent media attention for Black-owned businesses like hers, thanks to the Black Lives Matter movement, has given her an additional boost. Luttrell has been featured in three popular blogs.

“I had someone contact me recently from Microsoft and put in an order for 1,000 candles so she could send them as a nice gift to her employees who are working from home,” she says.

Luttrell’s ultimate vision, she says, is to go brick and mortar. “I would like to have a candle studio and bar,” she says. “People could come in and make their own candles but also still purchase some of mine. I’d host workshops, like a girls’ night or date night, and maybe post lessons on YouTube.”

How to sell art without wine and cheese

In a youth-oriented culture, it’s not easy getting older. Patti Curtis knows this well. For years, she worked as a product development executive in the cosmetics industry. Three years ago, at 53, after she was laid off, she decided to start a business where she could celebrate the achievements of people her age.

She rented a small space in Seattle’s gritty Georgetown district and opened the slyly named Fogue Studios & Gallery (for old fogey). It’s a non-profit that features only artists who are 50 and older. Her venture quickly expanded into a 6,000-square-foot space with 36 artists, propelled in part by Curtis’s website and marketing savvy. But then, in March, the city ordered businesses to close.

Like many brick-and-mortar outfits, Curtis turned what had been solely an online marketing presence into a shopping destination. She began offering virtual gallery tours and, after adding a shopping cart feature to her site, she now sells art exclusively online.

Fogue Studios is among many small businesses in the U.S. that are also considered ventures, and an example of an entrepreneur adopting digital methods to do business.

That’s not to suggest it has been easy: In April, while operating solely online, Fogue’s sales dropped 90% from the same period in 2019, says Curtis. Since then, sales have rebounded to 40% of what they were last June.

“It’s a tough sell convincing people to buy art online,” says Curtis. “It’s an event-driven business where you rely on openings and local art walks that can draw in 300 people in a day to drink wine and eat cheese. But the online sales have been enough to help my artists during this time.”

What could help more, she says, is the city stepping in to help entrepreneurs. For instance, it could offer tax breaks to landlords who rent to ventures that give back to the community.

“Helping businesses that are struggling, to give us a break on our taxes or the rent we pay is such a no-brainer,” she says. “Anything that would make us look more attractive to a landlord.”

In the meantime, Curtis is planning to use the impetus of the crisis to nudge her forward. She hopes to turn Fogue into a lifestyle brand, selling things like clothing to her mostly 50-plus customer base.

“I think there’s a big category for selling to people over 50 that most marketers overlook,” she says. “My motto is kind of like, ‘If not now, when? If not me, who?’ That’s the kind of person I am — a risk-taker. I put fear aside.”

The post When COVID-19 hit, these creative entrepreneurs hit the web appeared first on GoDaddy Blog.