When the COVID-19 crisis hit, Jim Masterson had to figure out how to massage a horse online.

For more than a decade, Masterson and his wife, Conley, have been the go-to experts for equine performance bodywork.

If your show horse got sore after a jumping competition, you could attend a workshop with a Masterson instructor to learn how to release the horse’s muscle tension through the unique Masterson Method.

The pandemic put a stop to the instructor visits and forced the Mastersons to think creatively about their business model and the horses they’ve dedicated their lives to helping.

Fortunately, they had access to an entire community of creative and like-minded entrepreneurs.

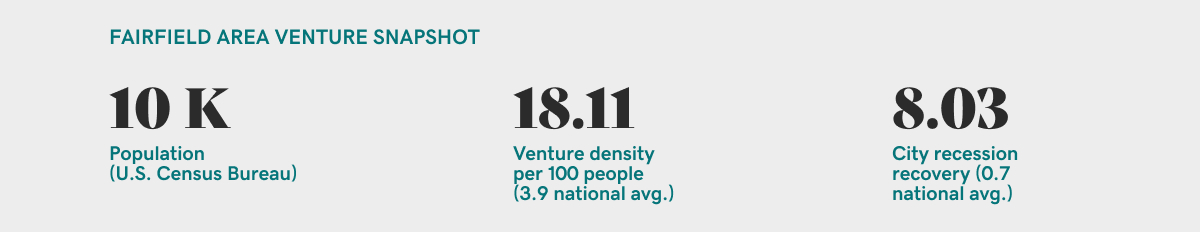

Based in the Corn Belt city of Fairfield, Iowa, the Mastersons are part of an entrepreneurial Shangri-La. The 10,425-person city, about 115 miles southeast of Des Moines, is home to a large number of small, internet-based micro-businesses that are emerging as a powerful driver of the U.S. economy and an important source of local economic resilience.

According to data that GoDaddy is compiling through a research initiative called Venture Forward, which studies the 20 million websites with domain names registered with the company, Fairfield has 18.11 of these ventures per 100 people. That’s nearly six times the average “venture density” of U.S. cities. GoDaddy’s research project has found that communities with higher venture density have lower unemployment and higher median income growth. They also bounce back better from economic downturns.

Fairfield made a strong recovery from the Great Recession of 2008.

Its prosperity score, a measure that looks at a range of economic factors, increased by 8 points in the years following the financial crisis compared with a 0.7 point increase for the country as a whole.

More recently, unemployment in the greater Fairfield area jumped in April, but at 9.4% it was still well below the national average of 14.7%.

“Having a strong entrepreneurial class of small agile businesses helps Fairfield not only survive, but thrive in fast-changing economies,” says Burt Chojnowski, the longtime president of the Fairfield Entrepreneurs Association.

People in Fairfield are confident in their community’s resilience in spite of the pandemic, even if some micro-businesses fail, he says. “People around here realize that a failed business isn’t a failure. It’s compost,” which provides everything from new wisdom to cheap office space and furniture for someone else.

Related: Four policy pillars that will encourage online microbusinesses

Statistically speaking, Fairfield has many of the hallmarks of other cities with high venture density.

More than 30% of its residents have a bachelor’s degree. Three-quarters of households have a high-speed internet subscription, including more than half of households with income below $20,000 per year, according to government statistics. It has a diversified economy, with several large companies that employ thousands of people.

But the driving force behind the town’s economy is what Chojnowski calls an entrepreneurial peer-to-peer network. Like many others, Masterson tapped the experience of others in his community to learn the basics of bookkeeping and marketing and turn his passion for helping horses into a viable business, he says.

Now, like many Fairfield micro-businesses, the Mastersons are using the web to reposition themselves for a fast-changing future.

For example, they are expanding their customer base to anyone willing to pay for an online subscription of either $20 or $40 a month. Among other things, that gives access to Facebook Live events, where Jim answers questions as horse owners watch a prerecorded video (shot by Conley) of him giving a certain type of massage. “It’s like a Zoom call,” says Masterson, “but with a horse.”

Related: Online micro-businesses can be an easy economic win for local governments

Innovate, and you shall be rewarded

Such inventiveness has been baked into Fairfield’s soil from the start.

Some of its earlier denizens became famous for creating category-making companies, from industrial agriculture equipment to infomercial production.

Starting in the late 1970s, young people began arriving by the micro-bus load to study transcendental meditation at what’s now called the Maharishi International University, founded by the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (who had taught the Beatles to meditate).

“We were a bunch of energetic young hippies who wanted to stay in the community, but didn’t want to be pig farmers or cashiers at Walmart,” says Eric Rusch, who arrived in 1979 and would go on, nearly three decades later, to launch the online home-baking business, Breadtopia.

Like Rusch, many of these meditation devotees started their own companies, from computer magazines to petroleum brokerages to accounting services. The TM philosophy magnified whatever was already in the air. Many locals credit their Yogi’s can-do teachings (“You will be rewarded 10,000 times over spiritually and materially”) for much of their later successes.

A few entrepreneurs quickly formed Internet Service Providers to deliver dial-up service; two decades later, it was one of the first towns to have high-speed fiber connectivity in homes.

When Burt Chojnowski arrived from the West Coast 20 years ago, he began advertising a Silicon Valley-style boot camp for internet entrepreneurs. He was shocked when 120 people showed up. By 1997, Wired had dubbed the area “Silicorn Valley.”

Chojnowski, of the Fairfield Entrepreneurs Association, says that over a third of the town’s workforce is self-employed and runs one or more micro-businesses, in large part because there are trusted sources of everything from marketing advice to start-up capital.

There’s even a newsletter by longtime resident Hal Goldstein, who arrived in town in 1979 to study meditation and now teaches entrepreneurship at Maharishi International University, called “The Meditating Entrepreneurs,” to share the collective wisdom.

He’s also published a companion book, “Meditating Entrepreneurs: Creating Success from the Stillness Within.”

Fairfield’s ventures share common attributes. Many were bootstrapped from personal savings or started with a few thousand dollars borrowed from friends and family.

And while there have been blockbuster success stories — one local who had failed at tofu and appliance businesses shocked his neighbors by selling his online marketing firm booksarefun.com to Readers Digest for $380 million in 1999 — many Fairfield entrepreneurs view their companies as lifestyle businesses.

They’re more likely to give away free instructional videos in order to build loyal followings than look to monetize every last minute of effort. “Plodding along, that’s my MO,” says Rusch, the Breadtopia CEO

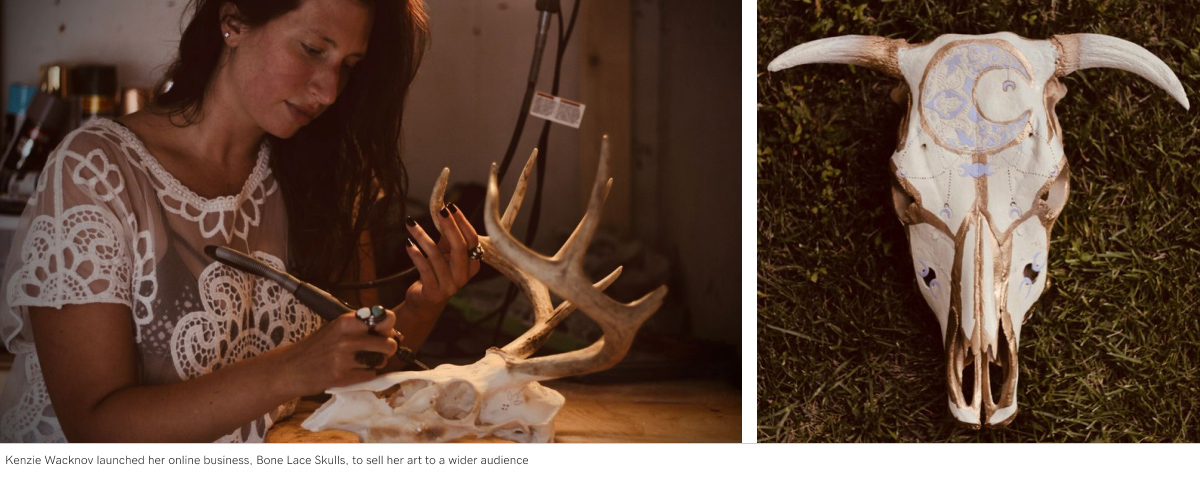

The venture-generating flywheel hasn’t slowed down. Kenzie Wacknov decided during the pandemic to turn her hobby of sculpting and painting animal skulls into a business. She’s now selling her art to people who find her online.

For Rusch, the wide reach of the web has presented a new challenge. The formerly “energetic young hippie” who started selling bread-making tools, ingredients and “starter” dough to DIYers back in 2006, had been planning to hand over the business to his stepson. Instead, COVID-19 has given rise to a shelter-in-place sourdough craze as novices try their hands at it.

Retirement, it seems, will have to wait for the 65-year-old. Says Rusch, “For now, it’s a hold-on-to-your-hat kind of thing.”

The post How tiny Fairfield, Iowa, became a micro-business capital appeared first on GoDaddy Blog.